In January of this year Maine’s highest state court, the Maine Supreme Judicial Court, also known as the “Law Court”, issued a decision called A.S. v. LincolnHealth.[1] This decision had a substantial impact on the process used to hold someone in a general hospital’s emergency department under Maine’s law for emergency involuntary admission to a psychiatric hospital. Below is a Q&A regarding this case:

What happened in the A.S. case?

Law enforcement took A.S. into protective custody and brought him to an emergency department for a mental health evaluation. Maine statutes allow for a person to be involuntarily admitted to a psychiatric hospital on an emergency basis.

The process used is set out on a one page application form created by the State of Maine and is commonly referred to as being “blue papered.”

The first section of this form is filled out and signed by the person who is seeking to “blue paper” an individual.[2] The second section is filled out and signed by a medical practitioner that certifies that they have examined the person and it is their opinion the person meets the statutory criteria for emergency involuntary admission to a psychiatric hospital.

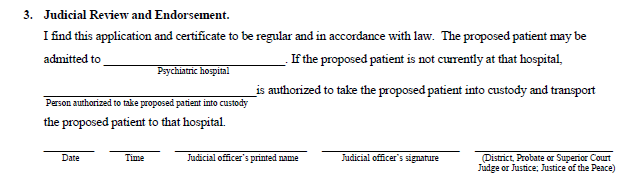

The third section of this form is called the “Judicial Review and Endorsement” section and it is required to have the name of the psychiatric hospital that is being proposed for the patient to be transferred to from the emergency room. Section 3 must be signed by a judicial officer.

At the time of A.S.’s detention, Section 3 looked like this:

The hospital emergency department had held A.S. for 30 days relying on this statute and filled out 16 blue papers, but never obtained the Part 3 “Judicial Review and Endorsement.” They argued that they were unable to so because they could not find a psychiatric hospital that would admit A.S. therefore were unable to fill in the blank with the name of a psychiatric hospital for the judicial officer to endorse the transfer to.

Was that allowed under the statute?

That was the issue in the A.S. case. While the statute contained language that allowed for a person to be held in an emergency department for an initial 24 hours and then, in certain circumstances, two 48 hour periods for a total of 120 hours, it did not address the issue of what would happen if this time limit was exceeded when an emergency department could not identify a psychiatric hospital to put in Section 3 of the form.

If the statute does not spell this out how did the Law Court interpret it?

The Law Court interpreted the statute as not requiring immediate release after 120 hours but also did not allow for the blue paper process to continue over and over again without obtaining a judicial endorsement. The Law Court stating:

Our interpretation of the plain language of the statute, however, does not mean that LincolnHealth was required to either discharge A.S. or transfer him to a psychiatric hospital at the end of the first 120-hour period. If the patient cannot be safely released after the entire 120-hour authorized hold period has lapsed and if there is still no psychiatric bed available, the hospital may “restart” the process.

This restart requires that a new application and certifying examination, including adequate and updated information relevant to the individual at that moment in time, be submitted for judicial endorsement within twenty-four hours after the 120-hour period ends. With a new judicial endorsement in hand, the hospital may then continue its efforts to find an appropriate placement for the patient and will not be required to discharge him. There is nothing in the statute that prohibits this practice, so long as the hospital immediately undertakes to secure judicial endorsement for every “new” statutorily authorized period of detention.

Did the Law Court give any further guidance?

Yes, they summarized their ruling as follows:

In summary, when a hospital determines that a person meets the requirements of [the statute] and it has a certificate from a medical practitioner that complies with [the statute], but there is no available psychiatric bed to which the person can be transferred, the hospital may detain the person for up to twenty-four hours only if it seeks to have the application for emergency hospitalization reviewed and approved by a judicial officer “immediately upon execution of [that] certificate.” With that approval, the hospital may then hold the individual for up to an additional ninety-six hours—one forty-eight hour period authorized by [the statute], and one forty-eight-hour period authorized by [the statute]—without additional judicial review so long as the hospital (1) periodically determines—medically—that the person continues to pose a likelihood of serious harm, [and] undertakes its best efforts to locate an inpatient psychiatric bed, and (3) notifies the Department of any detention exceeding twenty-four hours[3].

Why is this important?

Under this process, a judicial officer is going to be made aware that a person has been in an emergency department for any extended period of time.

How is this supposed to happen?

In March of 2021 the State of Maine changed it’s “Blue Paper” forms that the hospitals now must use.[4] One of the changes requires that any “blue paper” application submitted to the judicial officer must have attached to it all immediately preceding “blue paper” applications for the proposed patient.

Does the A.S. decision require the judicial officer to take any action when the number of “new” requests for authorized periods of detention in an emergency room reach a certain amount of time when added up together?

While the Law Court in the A.S. decision did not address this issue, they did emphasis the extraordinary nature of the power given to hospitals when using this process and the impact it has on the individual, stating:

Section 3863 and the other sections contained within article 3 authorize a hospital to do what it otherwise could not lawfully do—detain a person against his will. Section 3863 outlines the first step of that extraordinary process, a process that has the potential to deprive a person of his right to control where he is, what he does, and how he is treated. See Guardianship of Hughes, 1998 ME 186, ¶ 11, 715 A.2d 919 (explaining that involuntary commitment involves “a complete deprivation of a person’s liberty to the extent the person could lawfully be restrained by force from leaving the facility” (emphasis omitted)); Doe v. Graham, 2009 ME 88, ¶ 23, 977 A.2d 391 (“We have previously recognized that both the private and governmental interests associated with involuntary commitment due to mental illness are substantial.” (quotation marks omitted)).

Is there something that a person can do on their own?

Yes, if a person believes that they are being detained in an emergency room in violation of the law they can file an “Application for Writ of Habeas Corpus”.

Where would a person file this application?

Almost all of these types of applications are filed in the Superior Court.[5] And they would be filed with the Superior Court in the county where the emergency room the person is being held is located.

If the court hearing this Application for a Writ of Habeas Corpus finds that the person is not being held in accordance with the law does the court then have to order their release?

No. In the A.S. decision the Law Court stated:

A court facing a similar situation in the future—having to balance an individual’s liberty interests and his right to due process with concerns about his safety and the safety of the community—should understand that it has the ability to tailor any relief to effectively balance these competing interests.

Did the Law Court give any examples of what this might be?

Yes, they gave the following example:

For example, a court could tell the parties that it is granting the habeas petition but that it will stay for twenty-four hours the issuance of the mandate ordering release to allow the hospital to seek, through an application for involuntary admission, judicial endorsement of the patient’s continued detention.

If a person thinks they are being held in the emergency department and the hospital is not following the statute or the A.S. decision, how can they get help with filing an application for a Writ of Habeas Corpus?

They can call DRM and we will discuss the specific facts of their case.

If a person files an application for a Writ of Habeas Corpus on their own do they have a right to a court appointed lawyer?

That is unclear. The Law Court in a case called In Re Penelope W.[6] found that the ability for a person to proceed without representation at any key stages of an involuntary commitment proceeding is foreclosed by statute. Whether the rationale contained in In Re Penelope W. would be found applicable to a Habeas proceeding in accordance with the A.S. v. LincolnHealth decision is an open question.

If a person held in an emergency room files an application for a Writ of Habeas Corpus on their own are they prohibited from asking the court to appoint them a lawyer?

No. There is nothing that prohibits a person from asking for a court appointed lawyer when filing such an application.

If a person asks for the court to appoint them a lawyer but their request is denied what should they do?

They can call DRM.

[1] https://www.courts.maine.gov/courts/sjc/lawcourt/2021/21me006.pdf

[3] Citations have been omitted.

[4] https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/samhs/mentalhealth/rights-legal/involuntary/forms.html

[5] 14 M.R.S.A. § 5513 also provides applications can also be made “to any Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court”.